In the cryptocurrency ecosystem, Centralized Exchange play the role of a critical intermediary, where the majority of capital flows and trading activity take place.

Understanding the nature, operating mechanisms, and inherent risks of Centralized Exchanges is essential for users to accurately evaluate the role of this model and make appropriate choices between Centralized Exchanges and decentralized trading solutions.

What Is CEX?

CEX is a centralized exchange, which allows users to buy, sell, and exchange digital assets through a single managing organization. By nature, a centralized exchange is not a purely blockchain-based application. Instead, most core Centralized Exchange operations occur off-chain, while the blockchain only serves as the final settlement layer.

A centralized exchange can be viewed as an internal ledger system, where asset ownership is recorded and continuously updated in the exchange’s private database. The blockchain is only used when:

- Users deposit assets into the exchange, or

- Users withdraw assets from the exchange’s system.

This creates a fundamental difference between “trading on a centralized exchange” and “trading on the blockchain”.

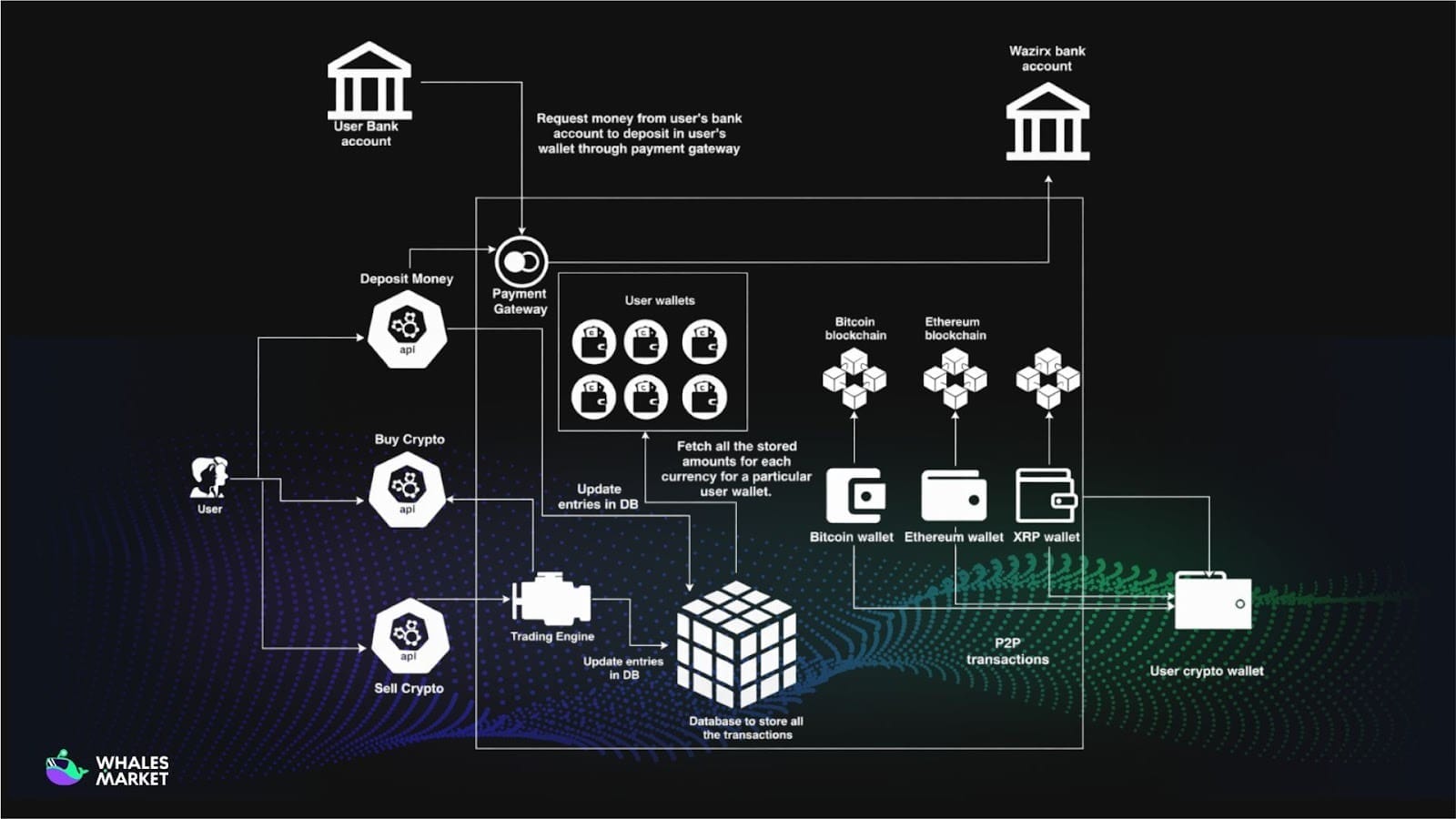

How CEXs Operate and Their Structure

A large-scale centralized exchange is typically composed of multiple system layers rather than a single monolithic platform. These layers include:

- Asset custody infrastructure

- Order book system

- Matching engine

- Settlement layer

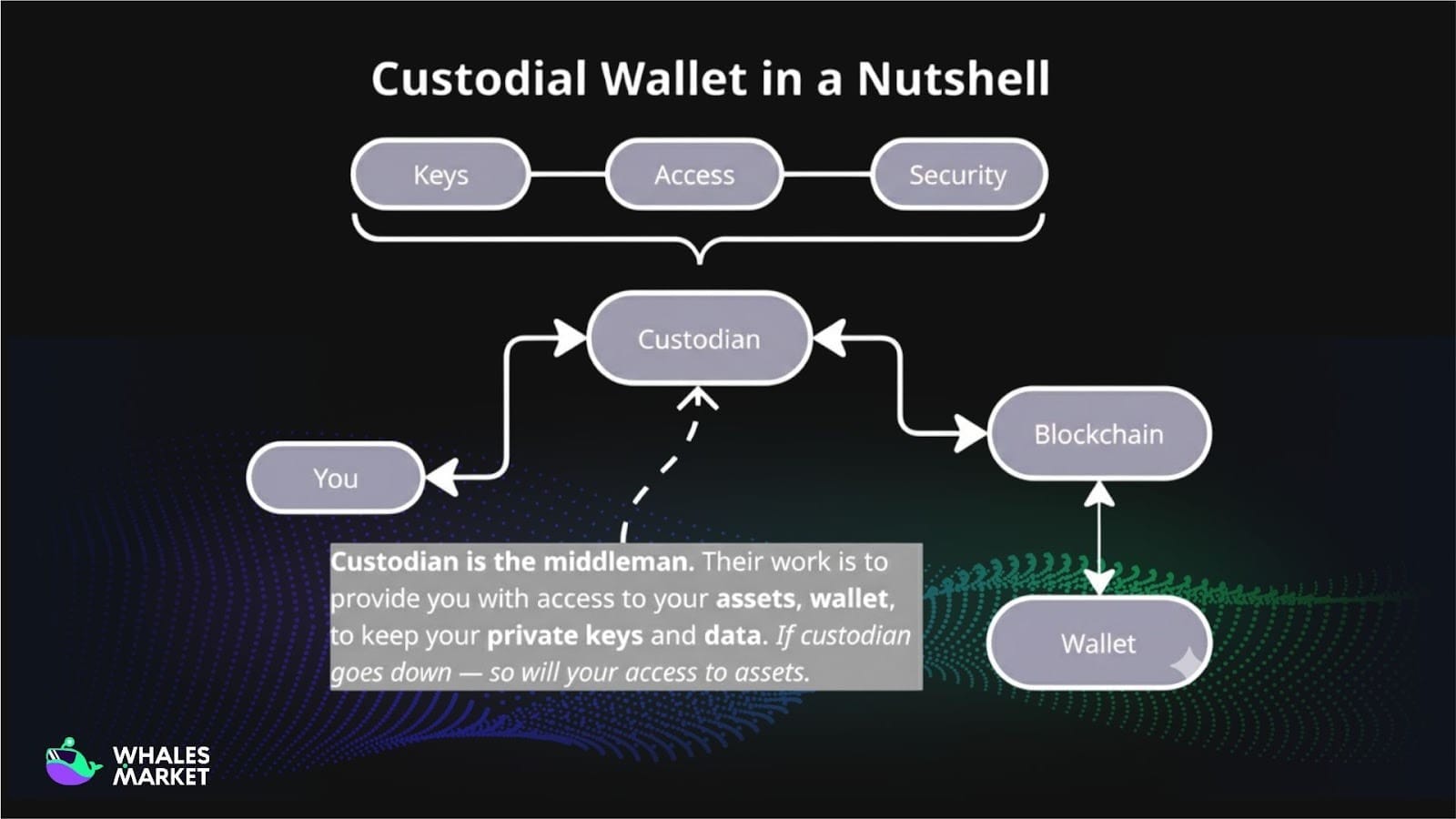

Asset Custody System (Custody Layer)

Once users deposit assets, those funds are transferred from their personal wallets to addresses controlled by the platform. At this point, the platform becomes the custodian, while users hold a claim on their assets rather than direct control.

Custody systems are typically divided into:

- Hot wallets: Used to support fast withdrawals and connected to the internet.

- Cold wallets: Store the majority of assets, isolated from the internet, often requiring multi-signature processes and manual approvals.

The allocation of assets between wallet types is a complex risk management challenge that directly impacts both liquidity and system security.

Internal Ledger

A critical point to understand is that the balance displayed in a Centralized Exchange account is not an on-chain coin. It is a numerical value in the exchange’s internal ledger, representing the exchange’s liability to the user.

When two users trade on the same Centralized Exchange, no blockchain transaction occurs. The exchange simply:

- Decreases the seller’s balance.

- Increases the buyer’s balance.

This entire process occurs instantly, with near-zero cost. This characteristic enables Centralized Exchanges to process tens of thousands of transactions per second, which current layer 1 blockchains cannot yet achieve.

Matching Engine

At the core of every centralized exchange is the matching engine, the system responsible for matching buy and sell orders. This engine operates similarly to those used in traditional stock markets, with order books organized by price and time priority.

Whenever a user places an order, the engine will:

- Verify order validity (balance, order type).

- Match the order with opposing orders in the order book.

- Update the internal ledger immediately upon execution.

Importantly, the matching engine operates entirely independently of the blockchain and is optimized for low latency, high stability, and parallel processing.

Settlement Layer

The blockchain only participates in the settlement process when users deposit or withdraw assets. During withdrawals, the exchange batches withdrawal requests, creates on-chain transactions, and broadcasts them from its wallets.

This leads to an important consequence: a Centralized Exchange can operate for extended periods without proving on-chain that it holds sufficient assets. This is the root cause of “proof of reserves” issues and historical trust crises involvingCentralized Exchanges.

Order Placement and Matching Mechanisms on CEXs

In centralized exchanges, all trading activities are processed through internal order books and matching systems managed by the exchange. Users do not trade directly with each other on the blockchain but submit orders to an internal market where the exchange coordinates liquidity and executes trades.

The two most fundamental order types reflecting how users interact with this system are market orders and limit orders.

Market orders allow users to buy or sell assets immediately at the best available price in the order book. Users do not specify a price and instead accept the price determined by the market at execution time.

This order type is particularly suitable under the following conditions:

- High market liquidity

- The need to enter or exit positions quickly

- Trade size is not too large relative to market depth

However, in low-liquidity conditions or for large orders, market orders can result in significant slippage. In such cases, a single order may be filled at multiple price levels, causing the actual execution price to deviate from the user’s initial expectation.

In contrast, limit orders allow users to predefine their desired buy or sell price. Orders are only executed when the market reaches the specified price, and while waiting, the order remains in the exchange’s order book. Mechanically, limit orders provide liquidity rather than consume existing liquidity.

The primary advantage of limit orders is price control, enabling users to better manage short-term market volatility. However, the downside lies in execution uncertainty:

- Orders may take a long time to be filled

- Orders may not be executed if the market price never reaches the specified level

| Feature | Market Order | Limit Order |

|---|---|---|

| Order execution time | Immediate | Slower or may not be executed |

| Order placement | Simple | More complex |

| Trading fees | Higher | Lower |

| Price control | No price control; execution price may vary with market | Full control over execution price |

Differences Between CEXs and DEXs

From an operational perspective, order placement and matching mechanisms highlight the central role of centralized exchanges in controlling trade flow and liquidity allocation. This is also the core difference between Centralized Exchanges and decentralized exchanged, where matching logic is executed directly on the blockchain.

| Aspect | CEX (Centralized Exchange) | DEX (Decentralized Exchange) |

|---|---|---|

| Asset custody | Exchange holds users’ assets and private keys | Users retain full custody of assets |

| Order execution | Off-chain matching via centralized engine | On-chain execution via smart contracts |

| Settlement | Internal ledger; blockchain used for deposits/withdrawals | Every trade settled on-chain |

| Control & governance | Managed by a central entity | Governed by protocol rules and code |

| Liquidity | High, aggregated in centralized order books | Fragmented, depends on liquidity pools |

| Speed & cost | Fast execution, low transaction cost | Slower execution, gas fees apply |

| Risk profile | Custodial, operational, and regulatory risks | Smart contract and protocol design risks |

On CEXs: Binance (or Coinbase)

When users place a BTC buy order on Binance, the order is sent to the exchange’s central servers. Binance manages the entire order book, executes internal matching, and then updates account balances for the relevant parties.

Binance controls transaction flow, validates orders, and allocates liquidity through internal funds or market makers. This enables fast execution and high liquidity, but users are fully dependent on the exchange and face risks if the platform is hacked or halted.

Key difference: The process occurs off-chain, with full control by the exchange.

On DEXs: Uniswap on Ethereum

When users swap ETH for USDC on Uniswap, the transaction is executed directly with smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain, without a central server. The smart contract automatically checks liquidity pools, calculates exchange rates, and executes the transaction on-chain.

There is no intermediary control; liquidity is provided by the community, and users retain control of their private keys.

Key difference: DEXs are slower and incur gas fees, but eliminate centralized risk, with most risks originating from on-chain code.

Advantages of CEXs

Centralized Exchanges offer several key advantages that optimize trading experience and market efficiency, including:

- High liquidity concentration: Centralized order books aggregate a large number of buyers and sellers, enabling efficient price discovery and low slippage, especially for large-volume trades.

- High performance and scalability: Off-chain order matching allows Centralized Exchanges to process thousands of transactions per second with low latency and minimal transaction costs.

- User-friendly experience: Centralized Exchanges provide intuitive interfaces, fiat on-ramps, customer support, and account recovery features, lowering entry barriers for new users.

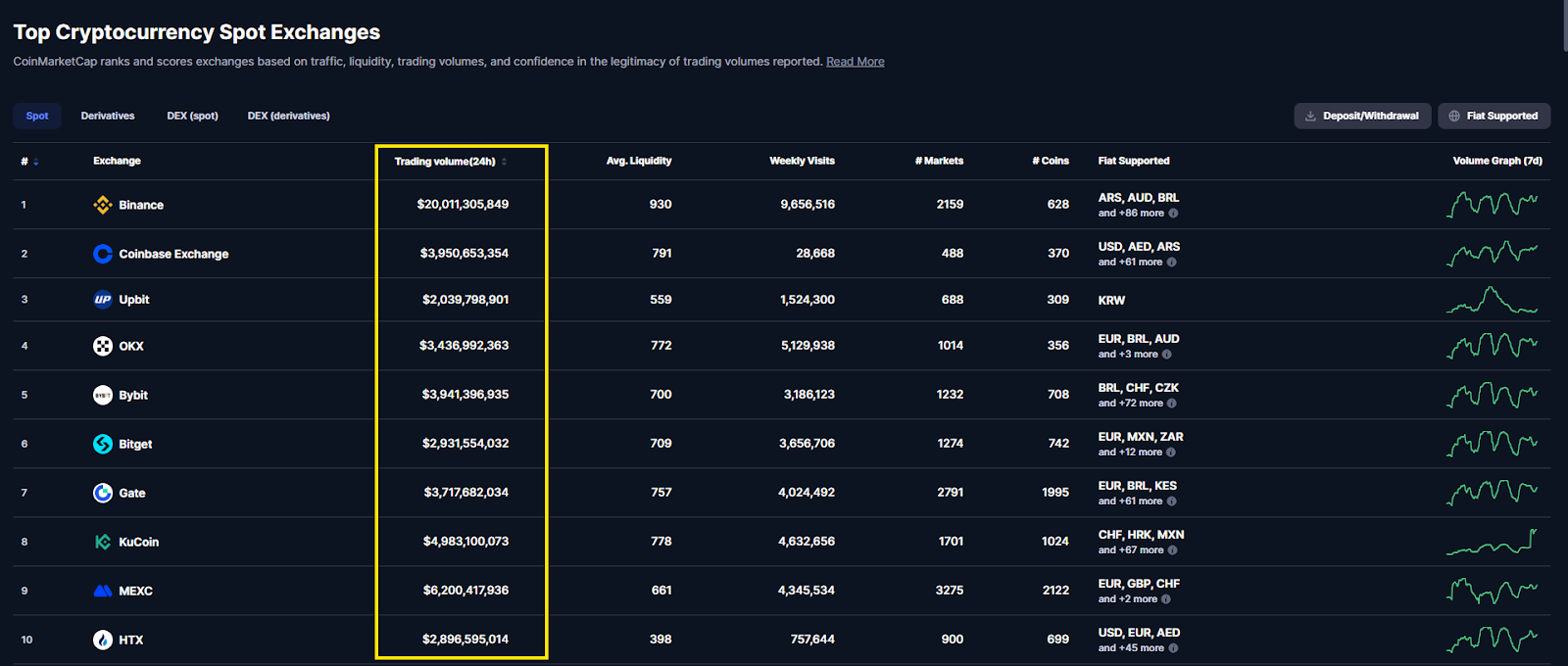

Binance is a typical example, processing billions of USD in daily volume. This creates a competitive advantage over DEXs, where liquidity is often fragmented and slippage is higher for large orders.

Disadvantages and Systemic Risks of CEXs

Despite these benefits, Centralized Exchanges also present notable disadvantages and systemic risks, including:

- Custodial risk: Users do not control private keys; deposited assets become liabilities on the exchange’s balance sheet.

- Trust dependency: Users must rely on the exchange’s solvency, internal controls, and risk management practices.

- Insolvency and misuse of funds: The collapse of FTX demonstrated how customer assets can be misappropriated, leading to massive losses during withdrawal surges.

- Security and operational failures: The failure of Mt. Gox exposed risks related to hacking, poor security practices, and weak internal oversight.

- Regulatory and operational intervention risk: Exchanges may freeze accounts, halt withdrawals, or suspend trading due to legal pressure or internal controls, often without immediate user recourse.

In the past, several major centralized exchanges collapsed due to security failures, mismanagement, and excessive reliance on user trust, resulting in significant user losses.

- Mt. Gox (2014): Hacked and lost approximately 850,000 BTC (≈ $460M), leading to bankruptcy and loss of user custody.

- FTX (2022): Collapsed due to misuse of customer funds, with an $8–9B shortfall, withdrawal freezes, and a Chapter 11 filing.

Criteria for Evaluating CEXs

There is no single “best” centralized exchange, as each platform has its own strengths and limitations. Choosing a suitable Centralized Exchange should therefore be based on practical evaluation criteria rather than popularity alone.

- Trading volume and liquidity are the most important indicators of an exchange’s quality. High trading volume usually reflects strong market participation, which helps reduce slippage, improve price discovery, and ensure faster order execution.

- Fees and fee structure vary significantly across exchanges. Users should consider not only trading fees but also withdrawal costs and maker–taker incentives, as these directly affect long-term trading performance.

- User support and operational reliability are particularly important during market stress or technical issues. Responsive customer support and clear communication enhance user trust and platform credibility.

- Security and risk management remain critical factors. Evaluating how an exchange manages asset custody, account protection, and internal controls can help users assess potential custodial and systemic risks.

- Supported assets and services should align with the user’s trading needs. A broader ecosystem may offer flexibility, but relevance is more important than feature quantity.

Conclusion

Centralized exchanges play a vital role in the cryptocurrency market through off-chain operations that deliver high performance, concentrated liquidity, and strong scalability. However, incidents such as Mt. Gox and FTX highlight the systemic risks of centralized models, particularly in asset custody and internal governance.

As a result, Centralized Exchanges are suitable for users prioritizing convenience and efficiency but require careful risk assessment and prudent exchange selection.

FAQs

Q1. Who are centralized exchanges most suitable for?

Centralized exchanges are best suited for users who prioritize convenience, fast execution, high liquidity, and access to customer support and fiat on-ramps.

Q2. Who may not be a good fit for using a CEX?

CEXs may be unsuitable for users who require full self-custody of assets, do not want to rely on a central intermediary, or prefer trust-minimized on-chain execution.

Q3. Why can CEXs process trades faster than blockchains?

Because order matching and balance updates occur off-chain using internal ledgers, CEXs avoid blockchain confirmation delays and gas fees.

Q4. Why are proof of reserves important for CEXs?

Since CEXs can operate without frequent on-chain verification, proof of reserves helps users assess whether an exchange holds sufficient assets to cover liabilities.

Q5. What happens if a centralized exchange halts withdrawals?

Users may temporarily or permanently lose access to funds, as withdrawals depend entirely on the exchange’s operational and regulatory status.

Q6. Can users trade on a CEX without interacting with the blockchain?

Yes. As long as funds remain within the exchange, trades are executed internally without any on-chain transactions.