According to CertiK's Hack3d Report, in the first half of 2025, more than $2.47B was lost to hacks, scams, and exploits, surpassing the total losses of 2024. As exploit techniques grow more advanced and attackers target both user accounts and contract-level flaws, understanding the red flags and defense strategies has never been more critical. So what is an exploit in crypto, and how does it work?

What is Exploit in Crypto?

In computer science, an exploit is a piece of code, sequence of commands, or technique that takes advantage of a vulnerability in software, a system, or a protocol. Its purpose is typically to gain unauthorized access, manipulate behavior, or extract value from the system. Exploits can target weaknesses in operating systems, applications, networks, or hardware, and their consequences range from minor glitches to severe security breaches.

In cryptocurrency, an exploit is an attack that takes advantage of a vulnerability in a blockchain protocol, smart contract, or decentralized application to achieve unauthorized results. This can include stealing funds, manipulating token or asset prices, bypassing system rules, or disrupting normal operations.

Exploits typically target components such as smart contracts, decentralized exchanges, lending platforms, or blockchain bridges. Attackers often leverage flaws in code logic, protocol design, or external inputs (like price oracles) to extract value or cause operational disruption.

Essentially, a crypto exploit is like discovering an unintended backdoor in a blockchain system that allows attackers to act outside the rules, often resulting in significant financial loss for users and projects.

Understanding Blockchain Security

Before examining how attackers exploit blockchain weaknesses, it helps to first understand why blockchain is generally seen as secure. At its core, a blockchain is a distributed ledger maintained across a network of computers, or nodes, where each block stores transaction data, a cryptographic hash, and a timestamp.

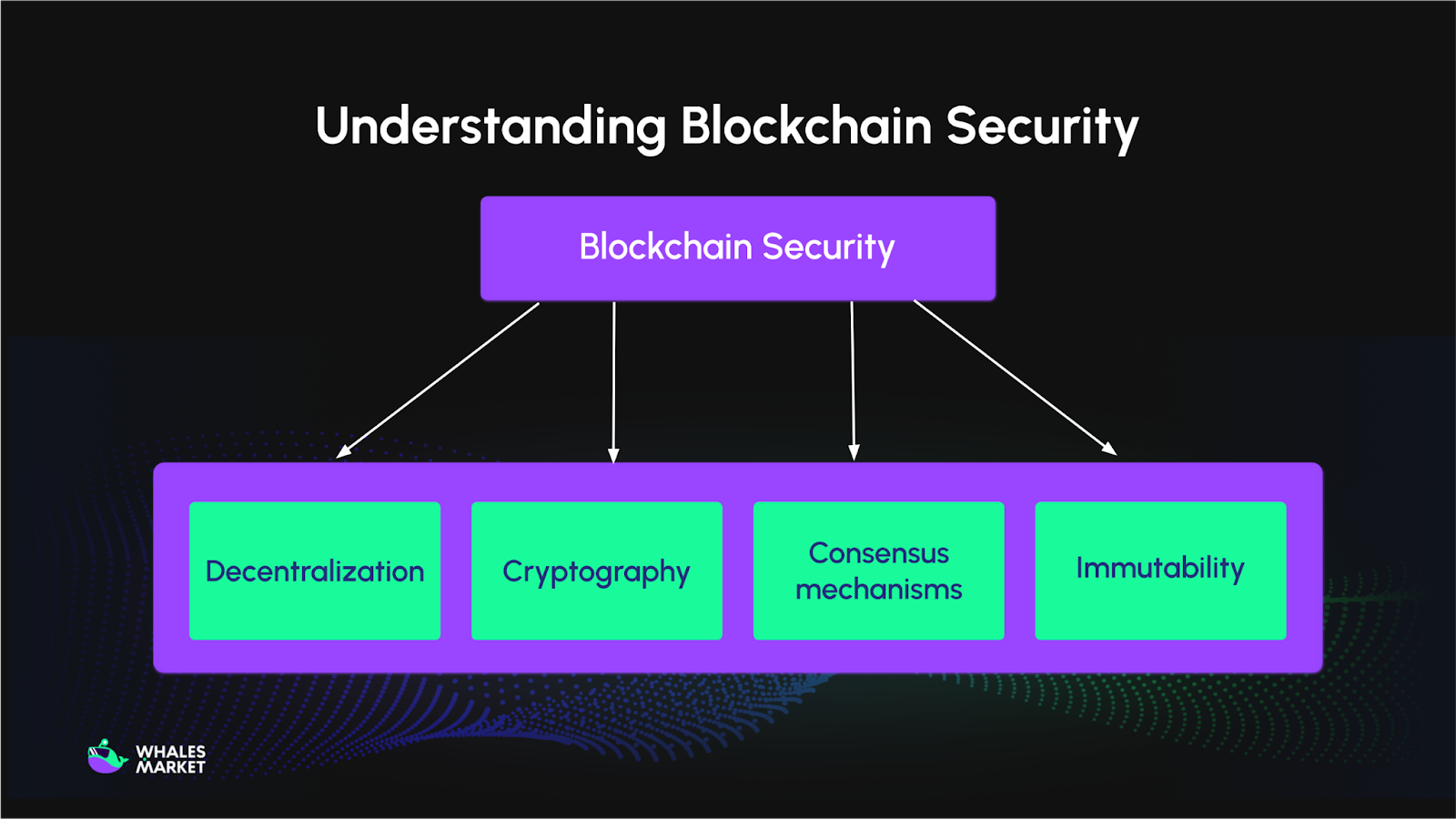

Blockchain security comes from several key factors:

- Decentralization: No single party controls the network, reducing the risk of central points of failure.

- Cryptography: Data is secured and verified using cryptographic algorithms such as SHA-256.

- Consensus mechanisms: This ensures that all nodes in the network validate and finalize transactions according to a fixed set of rules, protecting the blockchain from fraud or attacks like double-spending. Some popular consensus mechanisms such as Proof of Work (PoW), Proof of Stake (PoS)...

- Immutability: Once data is recorded on the blockchain, it is practically impossible to alter. Each block is linked to the previous one through a hash, so even a small change would invalidate the entire chain. To alter any data, an attacker would need to control a majority of the network, which is practically impossible on large, well-established blockchains.

Despite these core protections, blockchain security is not absolute. Vulnerabilities rarely stem from the underlying cryptographic or consensus mechanisms. Instead, they often arise from flaws in the implementation of smart contracts, misconfigurations of protocols, or the way external applications interact with the network, creating opportunities for malicious actors.

How Hackers Exploit Blockchain Vulnerabilities?

In blockchain, “exploitation” refers specifically to the moment when an attacker takes a discovered weakness and turns it into a real, damaging action. This is not the full hacking cycle, it is the phase where the attacker activates the vulnerability to manipulate smart contracts, protocols, or user balances.

A clear and accurate description of the exploitation phase in crypto looks like this:

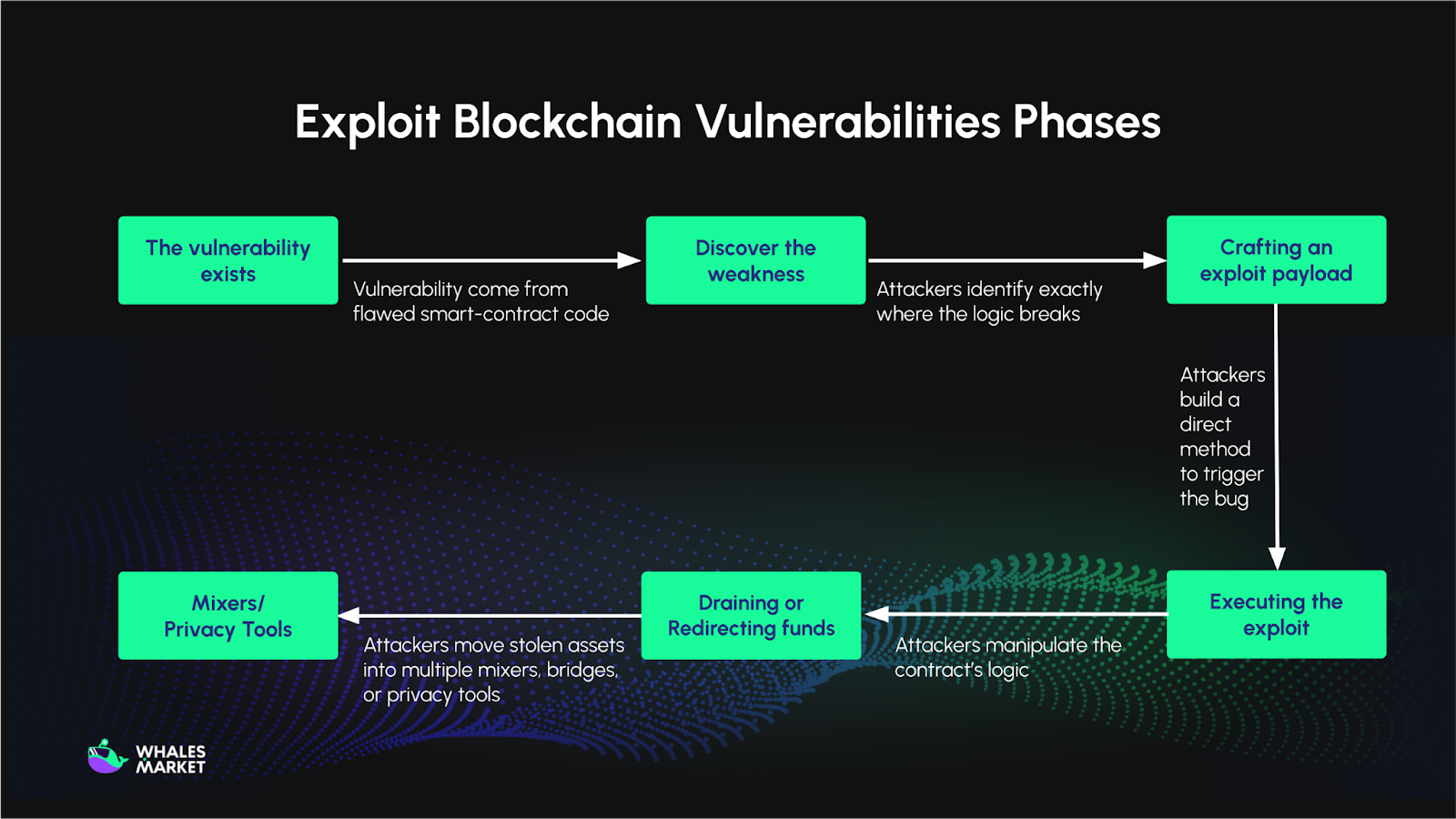

- The vulnerability exists: Most blockchain exploits come from flawed smart‑contract code, incorrect assumptions in protocol logic, misconfigured multisigs or oracles and unsafe upgrade mechanisms.

- The attacker discovers the weakness: Using manual review, scanners (like Slither, Echidna), or fuzzing tools, attackers identify exactly where the logic breaks. Examples include: a function that doesn’t check permissions, a math calculation that overflows and a reentrancy‑prone external call. At this point, the attacker understands what can be abused. Once a vulnerability is confirmed, the attacker prepares a method to trigger it.

- Crafting an exploit payload: The attacker builds a direct method to trigger the bug, such as a custom transaction script, a contract designed to manipulate the victim contract and an exploit kit that automates the attack. This is where the exploit becomes actionable.

- Executing the exploit: The attacker calls the vulnerable function or manipulates the contract’s logic to achieve unintended behavior. This can include draining liquidity pools, bypassing permissions, minting tokens, or redirecting assets.

- Draining or redirecting funds: After successfully manipulating the system, the attacker moves stolen assets into controlled wallets, often chaining multiple mixers, bridges, or privacy tools such as Tornado Cash to hide the trail.

This process mirrors the Exploitation Phase in the Cyber Attack Cycle, where attackers convert an identified vulnerability into real impact by executing malicious code or hijacking legitimate processes.

Types of Crypto Exploit

Before diving into individual attack methods, it’s important to understand that crypto exploits typically target weak points in code, protocol design, or operational controls. Some of the most common exploit types in the crypto ecosystem include:

Smart Contract Exploit

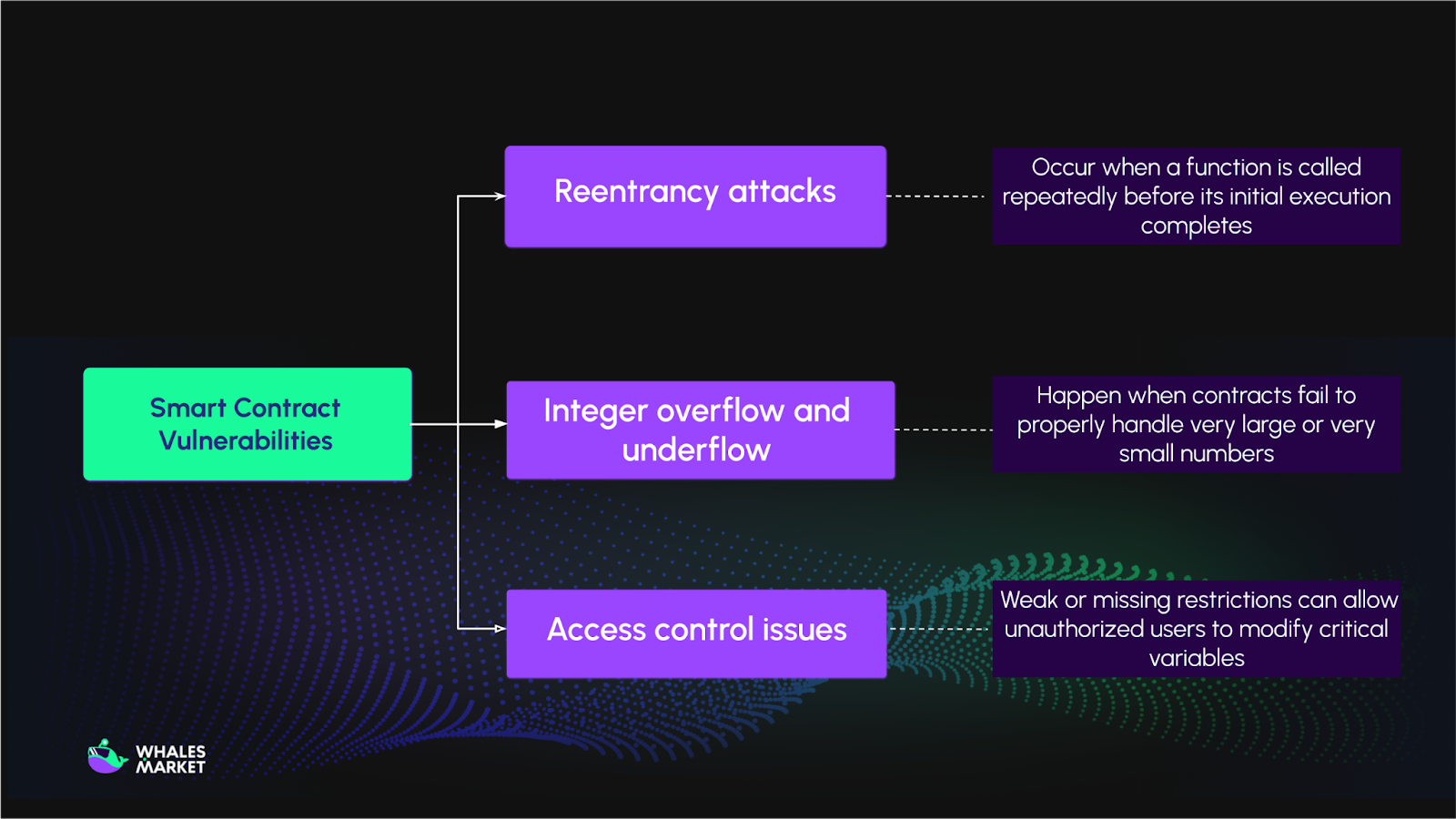

Smart contract exploits arise when flaws in self-executing code are exploited by attackers. Because smart contracts are immutable once deployed, bugs cannot be easily fixed, making careful auditing crucial, especially in the DeFi sector. Common vulnerabilities include:

- Reentrancy attacks: Occur when a function is called repeatedly before its initial execution completes, allowing attackers to drain funds. The 2016 DAO hack is a famous example of this exploit.

- Integer overflow and underflow: Happen when contracts fail to properly handle very large or very small numbers, letting attackers manipulate calculations or outcomes.

- Access control issues: Weak or missing restrictions can allow unauthorized users to modify critical variables or perform administrative actions.

Exploits in DeFi Protocols

DeFi platforms offer blockchain-based services such as lending, borrowing, yield farming, and cross-chain transfers. While innovative, they are exposed to several types of exploits:

- Flash loan attacks: Hackers exploit protocols that allow instant, uncollateralized loans (called flash loan) within a single transaction. By borrowing large amounts of assets without upfront collateral, they can manipulate token or asset prices on vulnerable platforms (e.g., decentralized exchanges or lending protocols) and extract profits before the transaction is finalized.

- Oracle manipulation: Attackers tamper with external data feeds (oracles) to mislead protocols, profiting from price discrepancies.

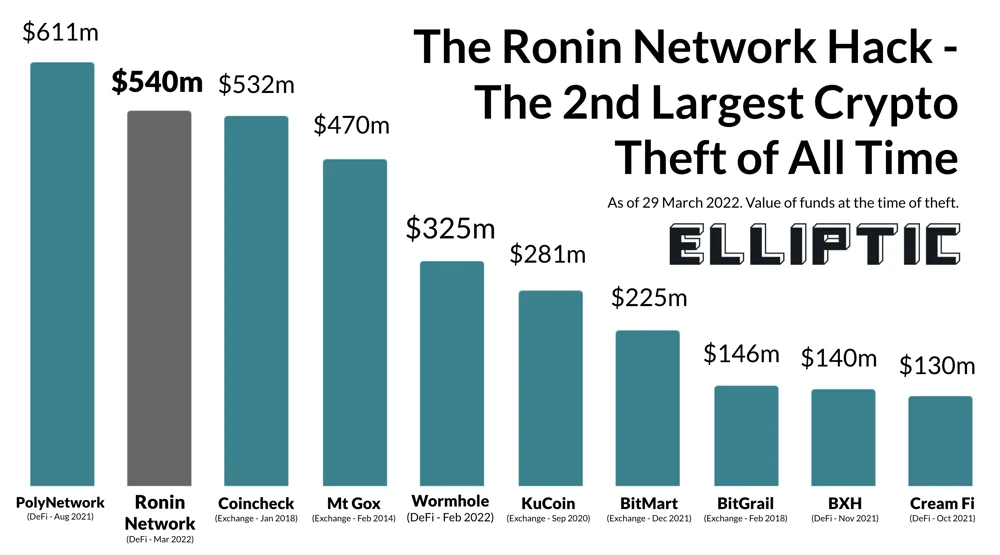

- Cross-chain bridge exploits: Vulnerabilities in bridge smart contracts or compromised validator keys allow attackers to drain assets across blockchains. Examples include the Ronin Bridge hack, which resulted in approximately $600M in losses, and the Harmony Horizon Bridge hack, which caused around $100M in losses.

The rapid growth of DeFi has created opportunities for these exploits, often resulting in losses of millions of dollars in cryptocurrency.

Other Blockchain Exploits

Beyond smart contract bugs, attackers can exploit different layers of the blockchain ecosystem, including:

- Unchecked external calls: When a contract calls another contract without properly handling errors, it can lead to unintended behavior and loss of funds.

- Timestamp dependence: Relying on block timestamps for critical operations can be risky, as miners can slightly manipulate timestamps to influence contract outcomes.

- Network-level attacks: Targeting the underlying internet infrastructure can disrupt communication between nodes and compromise the blockchain network.

Biggest Exploits in Crypto

PlayDapp (2024) - Access-control exploit

PlayDapp is a blockchain gaming platform and NFT marketplace on Ethereum, allowing games to share in‑game assets via the PDA token. Between February and March 2024, the platform suffered two consecutive attacks.

The attacker exploited an admin access-control vulnerability in the smart contract, gaining the ability to mint new tokens. Using this privilege, they minted 1.79B PDA tokens and swapped them for ETH through decentralized exchanges. This attack represents a privilege escalation exploit caused by improper admin permission locking. The total estimated loss was approximately $290M, making it the largest exploit of 2024.

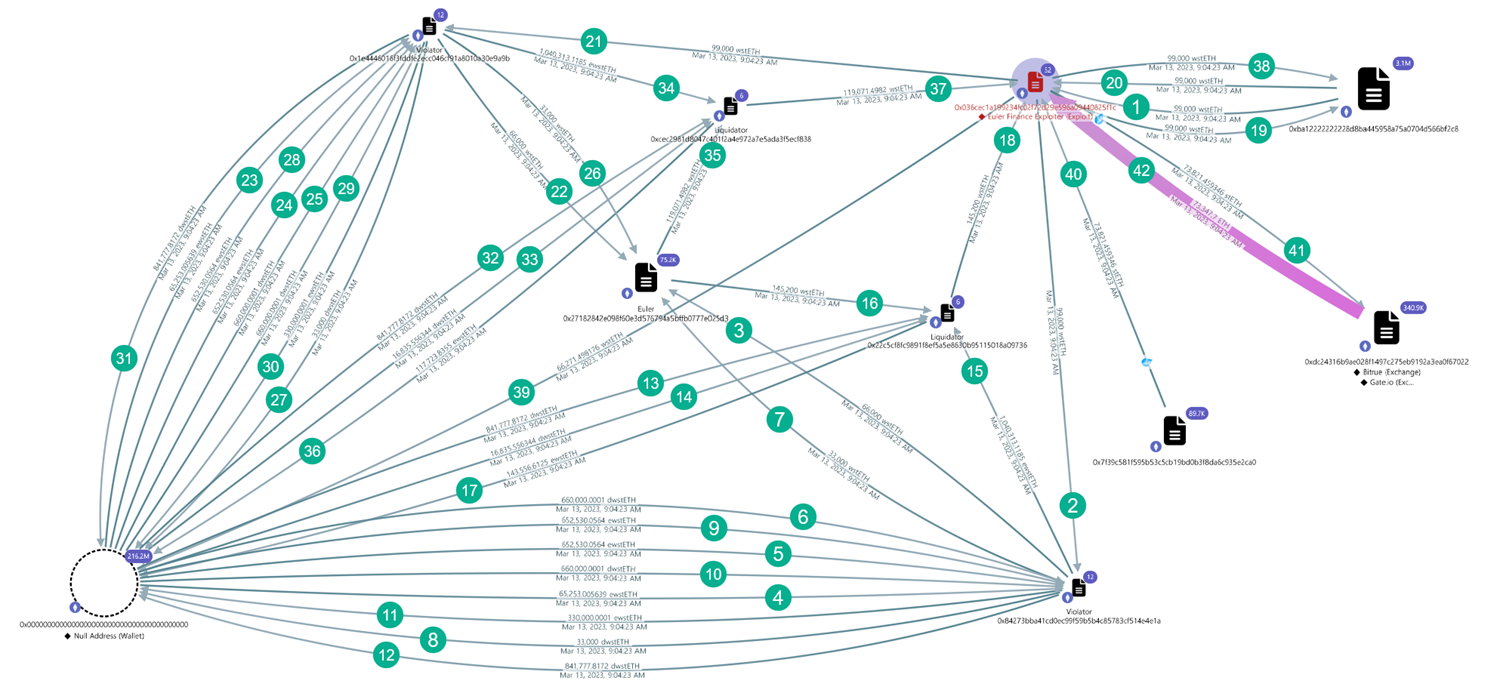

Euler Finance (2023) - Logic + Flash-loan exploit

Euler Finance is a lending and borrowing protocol on Ethereum, similar to Aave or Compound but designed with modular and capital-efficient mechanisms. On March 13, 2023, attackers executed a flash-loan exploit that leveraged a logic flaw in the donateToReserves() function combined with the liquidation module.

This allowed them to over-leverage positions, manipulate collateral and debt accounting, and drain the protocol without repaying assets at fair value. This incident is classified as a smart contract logic exploit, highlighting a flaw in how the protocol modules interacted with over-collateralized assets. The total damage was approximately $197M, including DAI, USDC, stETH, and WBTC.

Ronin Bridge (2022) - Validator set exploit

Ronin Bridge is a sidechain developed for Axie Infinity, enabling asset transfers between Ethereum and Ronin. The bridge relied on nine validators, requiring at least five signatures to approve withdrawals. On March 23, 2022, the attacker group Lazarus compromised five of the nine validator keys through social engineering, malware, and attacks on Sky Mavis’ centralized validator infrastructure.

With control of the majority of signatures, the attackers executed two fraudulent withdrawal transactions, draining 173,600 ETH and 25.5M USDC. This was a protocol-level exploit, as it involved compromising the validator quorum rather than individual private keys. The total loss was approximately $540M, marking it as the largest exploit in blockchain history since Poly Network.

Curve Finance (2023) - Vyper compiler bug exploit

Curve Finance is a leading automated market maker (AMM) for stablecoins and similar assets, with billions in total value locked, forming a core part of the DeFi ecosystem. On July 30, 2023, several Curve pools written in Vyper (versions 0.2.15–0.3.1) contained a compiler bug that caused the reentrancy guard to malfunction.

Attackers exploited this vulnerability to perform reentrancy calls and drain liquidity from the pools. This was a compiler-level exploit, notable because the vulnerability originated in the compiler itself rather than Curve’s smart contract code. The total estimated loss was around $70M, affecting the alETH, msETH, and pETH pools.

Radiant Capital (2024) - Multi-sig access-control exploit

Radiant Capital, an omnichain lending protocol operating on Arbitrum and BNB Chain, became the target of one of the largest exploits in 2024. In mid‑October 2024, the multisig wallet used to manage protocol upgrades was compromised by attackers. Once in control, they deployed a malicious contract upgrade that altered how the system accounted for assets, enabling unauthorized withdrawals from lending pools.

By exploiting the modified contract, the attackers drained approximately $50-53M in assets, transferring funds through multiple intermediary wallets and mixing them via Tornado Cash. Upon detecting the breach, Radiant Capital promptly paused the Arbitrum and BNB Chain markets for investigation and confirmed that no user funds outside the affected pools were at risk.

How to Detect and Prevent Blockchain Exploits

Although blockchain is often praised for its security and decentralization, vulnerabilities still exist that can be exploited by attackers. Protecting blockchain networks, smart contracts, and user assets requires a combination of secure development practices, operational safeguards, monitoring tools, and user education.

For Projects: Preventing Blockchain Exploits

Blockchain networks and smart contracts, while secure by design, can still have vulnerabilities. Projects can reduce risks with the following measures:

- Secure smart contracts: Conduct regular audits using automated tools and manual code reviews. Follow best coding practices: use established libraries, write clear and maintainable code. Apply formal verification to ensure contracts operate as intended and have no exploitable flaws.

- Protocol and software maintenance: Keep nodes and software up to date to address known vulnerabilities. Test security improvements thoroughly before deployment.

- Monitoring and analytics: Use blockchain analytics platforms to detect suspicious transactions and exploit patterns. Implement transaction monitoring and behavioral detection to catch unusual activity early. Configure alerts and risk rules for timely response while minimizing false positives.

- System security measures: Use multi-factor authentication (MFA) and intrusion detection systems (IDS). Trace transactions flow across chains to detect suspicious or illicit activity.

For Users: Reducing Risk of Asset Loss

Human error is a major vulnerability. Users can minimize risk with these practices:

- Private Key Security: Store keys offline using hardware wallets. Enable multi-signature wallets for critical transactions. Activate two-factor authentication (2FA) on wallets and exchanges.

- Awareness and Education: Recognize phishing emails, suspicious links, and social engineering attempts. Verify projects, smart contracts, and platforms before transferring assets.

- Smart Contract Approvals: Only approve the exact amount of tokens needed for a transaction. Avoid granting unlimited token approvals, which can expose your wallet to unnecessary risk if a contract is compromised.

- Monitoring Tools: Track transaction history and review security reports from trusted wallets or analytics platforms. Limit interactions or withdraw funds from unverified or high-risk projects.

Conclusion

Although blockchain provides a decentralized and secure framework for storing data and conducting transactions, it still has weaknesses. Attackers can take advantage of flaws in blockchain protocols, smart contracts, or user security to carry out malicious actions, including stealing cryptocurrency or manipulating DeFi platforms.

By identifying potential risks and implementing protective measures for both networks and the applications running on them, users and organizations can reduce the likelihood and impact of blockchain-related attacks.

FAQs

Could blockchain technology be hacked?

Yes. Despite its strong design, blockchain systems have been and can be compromised via network attacks (like DDoS, Sybil, routing), smart-contract bugs, wallet flaws, and more. Many of these risks come from implementation mistakes or weak assumptions, not just fundamental design.

Are hackers exploiting blockchain security vulnerabilities as their main source of revenue?

Not always as the “main” source, but security flaws in blockchains are certainly a major target: attackers exploit contract bugs, consensus weaknesses, and user-side vulnerabilities to steal funds. The financial incentive is strong, especially because successful exploits can yield large sums.

What are some examples of blockchain attacks?

Some real-world attacks include: 51% attacks, where a miner or group gains majority control and can double-spend; flash loan exploits that abuse unsecured lending contracts; rug pulls, in which project creators abscond with user funds; and cryptojacking where devices are hijacked to mine crypto for the attacker. Other vectors include phishing (to steal private keys) and DDoS on node infrastructure.

What are the most common blockchain attack vectors?

The most frequent vectors include: network-level attacks (e.g., partition, routing, DDoS), wallet vulnerabilities (weak key generation, flawed signatures), and smart contract bugs (reentrancy, access control). Additionally, consensus-level risks (e.g., 51% or long-range attacks) are a serious concern.