A 51% attack occurs when an individual or a group controls more than half of a network’s mining power, allowing them to bend the rules of the system. With this majority control, they can reverse transactions, perform double spending, and disrupt the normal operations of other miners.

This article focuses on what 51% attack is, how a 51% attack works in practice, why smaller networks are more likely to become targets, and several notable case studies such as Ethereum Classic, Bitcoin Gold, Litecoin Cash, and the early, sensitive phase of Bitcoin.

What is 51% attack?

A 51% attack is a form of attack on a blockchain network, especially those using the Proof of Work (PoW) consensus mechanism. In this scenario, an individual, group, or organization controls more than 50% of the total computational power (hash rate) of the entire network.

With this level of control, the attacker can manipulate the blockchain’s public ledger, causing network disruptions, reversing transactions, or preventing other miners from participating.

Why attempt a 51% attack?

This idea is often linked to Bitcoin because it is the most well-known Proof of Work Network. But a 51% attack can apply to any PoW blockchain. It is also worth clarifying what it is not: it is not a traditional “hack” like stealing private keys.

Instead, it is an abuse of the blockchain’s consensus mechanism to gain majority control. It usually does not permanently destroy the network, but it can cause serious financial damage and quickly undermine trust.

So why would someone try it?

- Profit from double spending: The most common motive is to spend coins, receive goods or funds, then reorganize the chain to erase that payment. This allows the attacker to keep the coins while still getting the value. In practice, the easiest targets are fast settlement situations like exchanges, bridges, or merchants that accept low confirmation counts.

- Censorship and disruption: With majority control, an attacker can selectively exclude or delay transactions, effectively censoring certain users, addresses, or applications. Even if this does not directly generate revenue, it can still be used to disrupt the network, cause outages, and damage credibility.

- Market manipulation and shorting: An attacker might short the asset first, then launch the attack to trigger panic, exchange halts, or delistings. In this case, the chain reorg is less about stealing funds and more about collapsing confidence and price.

- Extortion or pressure tactics: Attackers can use the threat of repeated reorgs or ongoing censorship to pressure exchanges, projects, or teams into paying a ransom, changing policies, or offering other concessions.

What does the attacker actually gain? Mainly, they gain the ability to reorganize recent blocks and invalidate their own previous transactions, which enables double spending. They can also censor transactions and undermine finality guarantees.

However, they generally cannot create coins from nothing, steal coins from wallets they do not control, or change protocol rules unless the wider node ecosystem accepts those changes.

Why is it expensive and rare on large networks?

Because the attacker must sustain majority control long enough for the reorg to stick. That typically requires enormous cost: hardware, electricity, logistics, or renting hashpower at scale. There is also a high risk the market reacts quickly: exchanges raise confirmation requirements, deposits get paused, and the attacker’s window to profit closes fast.

On mature networks, the cost and difficulty usually outweigh the potential payout, which is why 51% attacks are more commonly discussed in the context of smaller PoW chains with lower total hashpower.

How does a 51% Attack work?

Because a blockchain is maintained by a distributed network of nodes, all participants cooperate to reach consensus. This is one reason blockchains are considered highly secure: The larger the network, the harder it is to overpower the system or rewrite its history.

For a large PoW network like Bitcoin, pulling off a 51% attack is extremely difficult because the cost of controlling the majority hash rate is enormous. On smaller PoW chains with lower total hashpower, the same attack can be much more realistic. In general, the process starts like this:

Step 1: Controlling more than 51% of the hash rate

To understand how a 51% attack plays out, start from the moment the attacker gains majority mining power. Instead of just a few scattered machines, they own or control a large number of ASIC miners, rent additional hash rates from mining pools, or collaborate with other large mining groups.

On smaller networks, where the total hash rate is already low, gathering more than 51% of the network’s power is not impossible, it is mainly a matter of money and coordination.

Majority control can be used in different ways, but the most common goal is double spending. The steps below focus specifically on how an attacker executes a double spend.

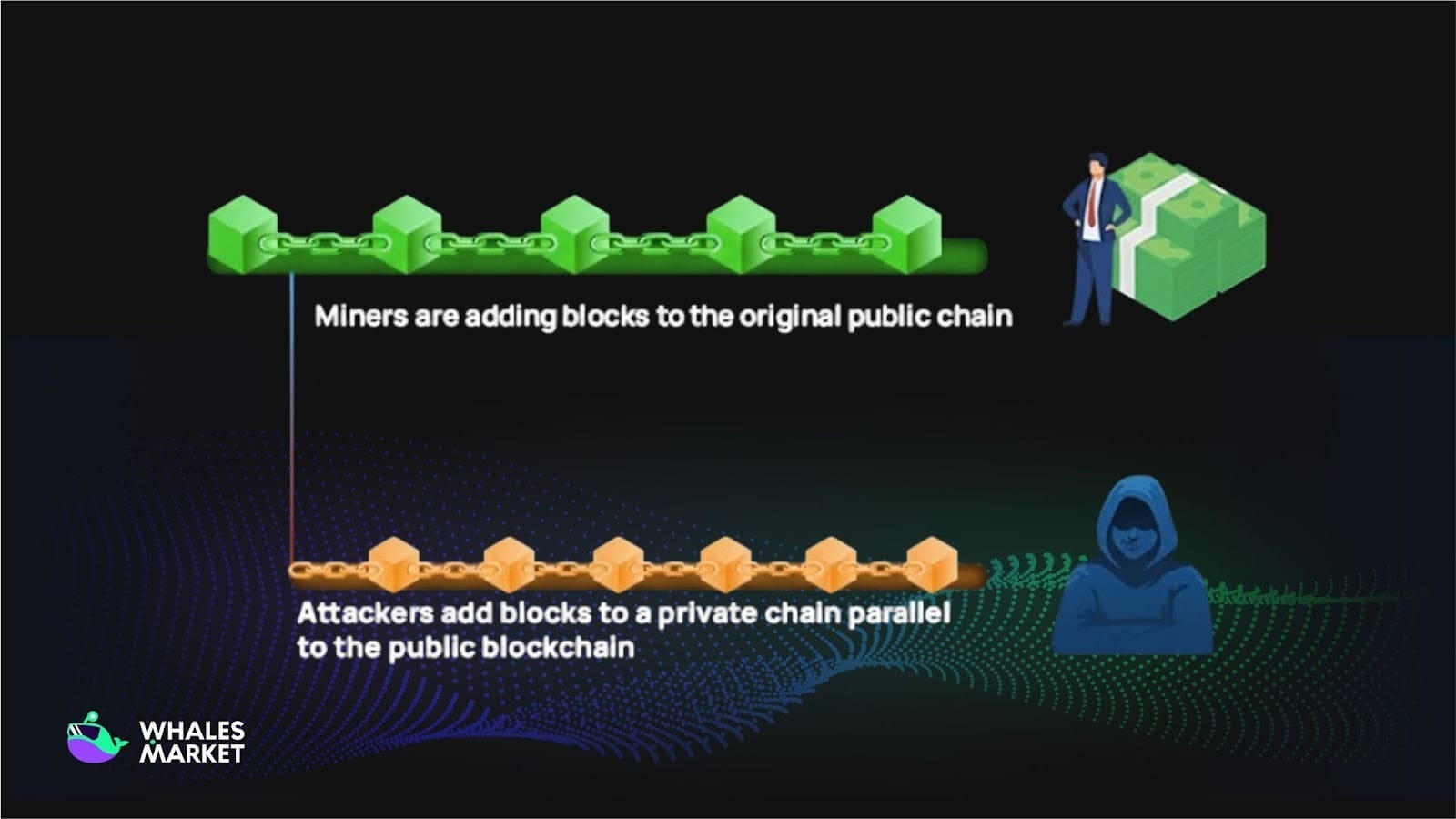

Step 2: Mining a private chain

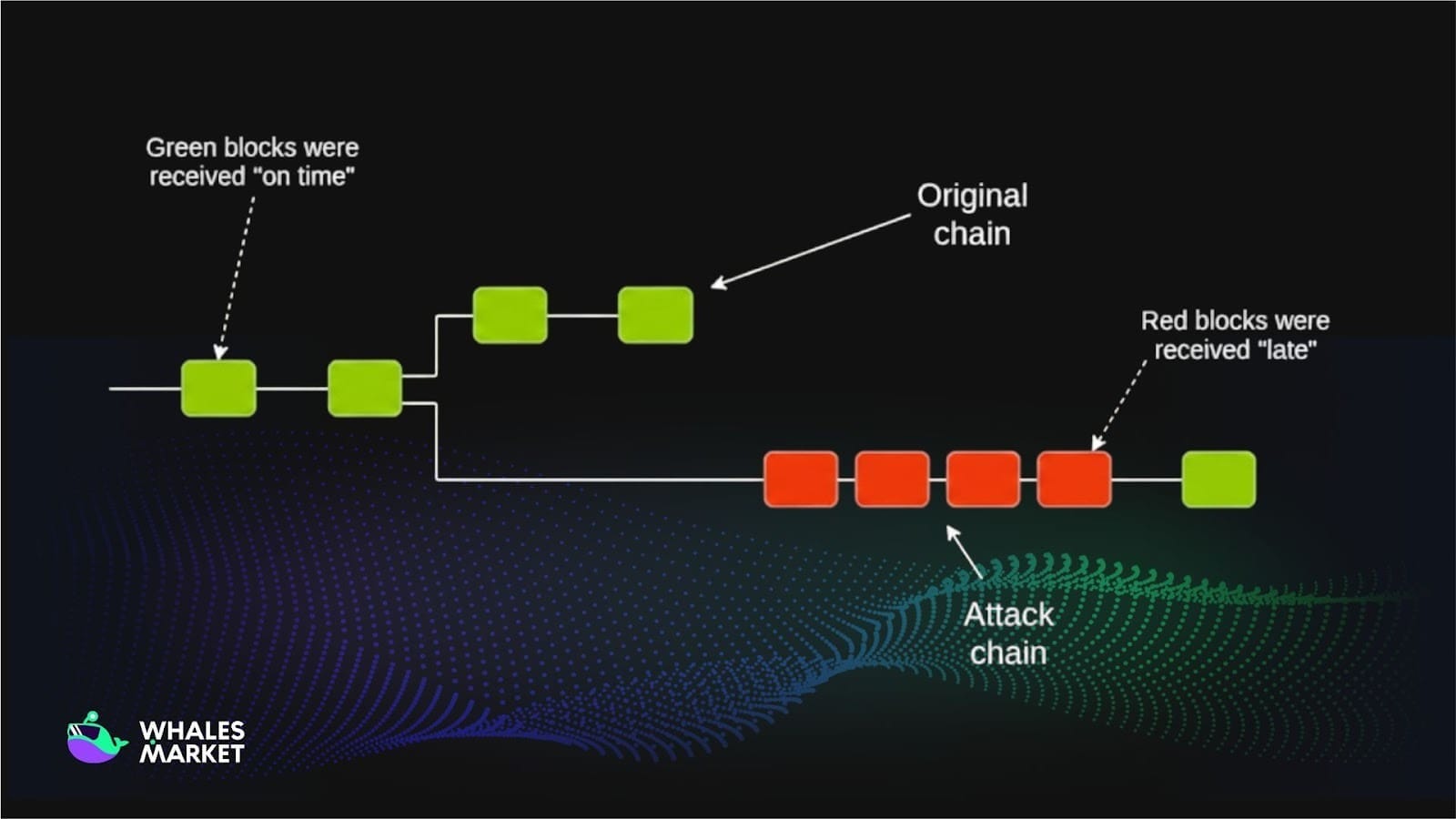

Once the attacker controls a majority of the hash rate, they move to the next step: quietly mining a private chain in parallel with the public chain.

On the public chain, everything still looks normal. The attacker can broadcast a payment to a merchant (for example, paying coins to buy goods), and the merchant may see the transaction confirmed.

However, on the attacker’s private chain, that payment is intentionally left out, so those coins are treated as if they were never spent. In other words, the attacker’s wallet balance on the private chain remains unchanged. This sets up a potential double-spend once the attacker later reveals the private chain.

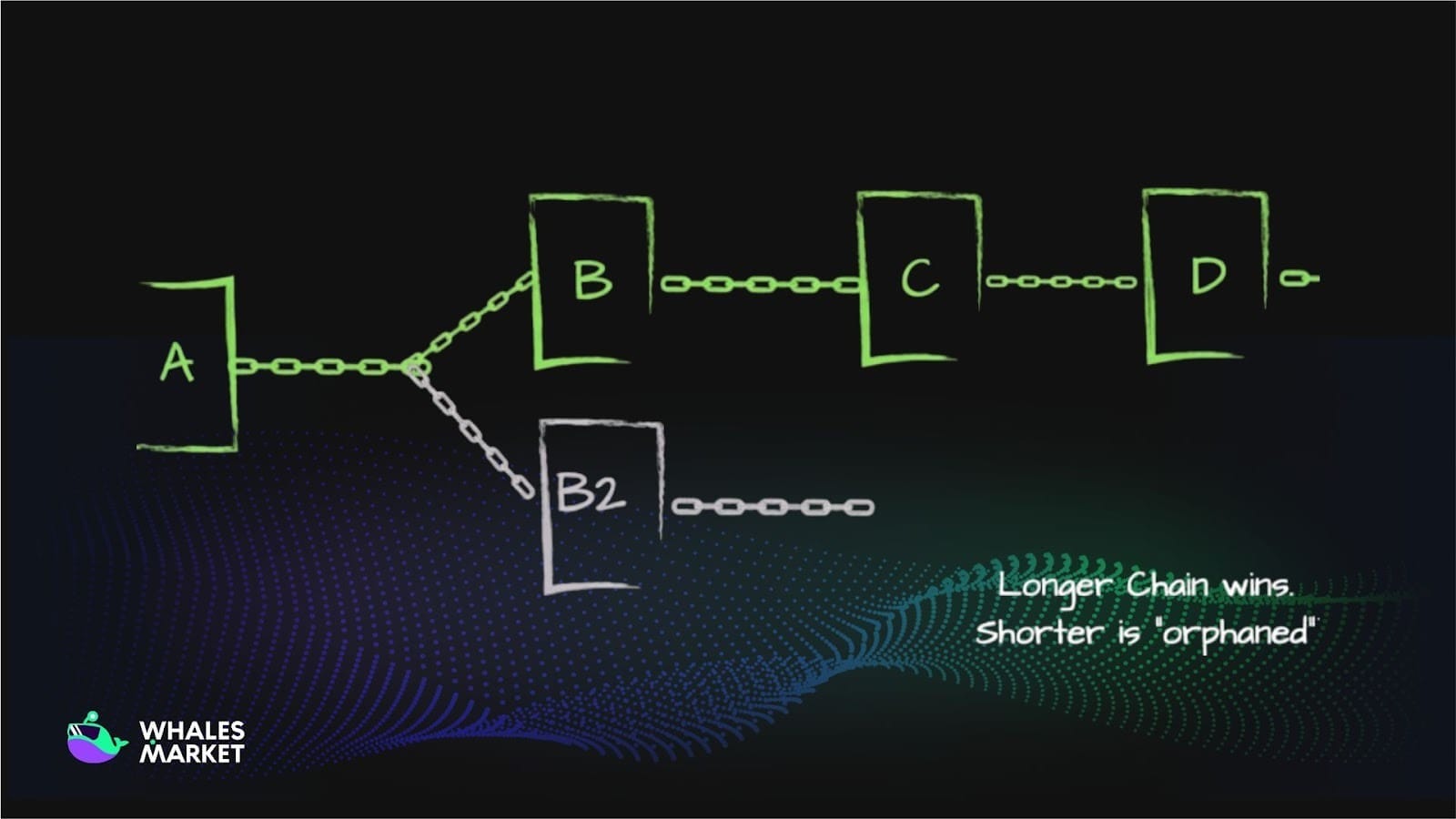

Step 3: Overtaking the main chain with private chain

It is crucial to know that the longest-chain rule is a principle in blockchain, where the valid chain is the one with the most accumulated work, usually measured by total proof-of-work. Nodes automatically follow this chain because it represents the greatest amount of mining effort. This helps the network stay consistent and resist attacks.

Because the attacker controls a majority of the hash rate, their private chain grows faster and eventually overtakes the public chain in cumulative proof-of-work. At a suitable moment, the attacker broadcasts this entire chain to the network. Nodes in the system, which follow the rule that the longest chain is considered valid, will accept the new chain and discard the old one.

Transactions that were previously considered valid now disappear and the payment is reversed. The attacker has already received goods or assets in the real world while still keeping the original funds on the new chain. This is a complete double spending scenario.

Beyond double spending, with majority hash rate in hand, the attacker can distort the experience of other users by blocking or delaying transaction confirmations, excluding certain transactions from blocks, or making it extremely difficult for other miners to find new blocks, turning mining into an almost monopolized activity.

Case Studies of 51% Attack

Ethereum Classic (ETC)

When talking about 51% attacks, one of the most well known cases in recent years is Ethereum Classic (ETC). This is a PoW blockchain with a relatively low hash rate, and its mining algorithm is compatible with many common machines, which makes renting hash power via services like NiceHash relatively cheap.

In 2019 and 2020, ETC was repeatedly attacked. The attacker rented hash rate, secretly mined a private chain, and carried out large double spends through exchanges. Within just a few rounds, the amount double spent exceeded $1M, forcing major exchanges like Coinbase to increase the required number of confirmations to 10,000 blocks, equivalent to several days of waiting.

This incident made the community realize that mid tier PoW chains without sufficient hash rate are almost “open doors” for 51% attacks.

Bitcoin Gold (BTG)

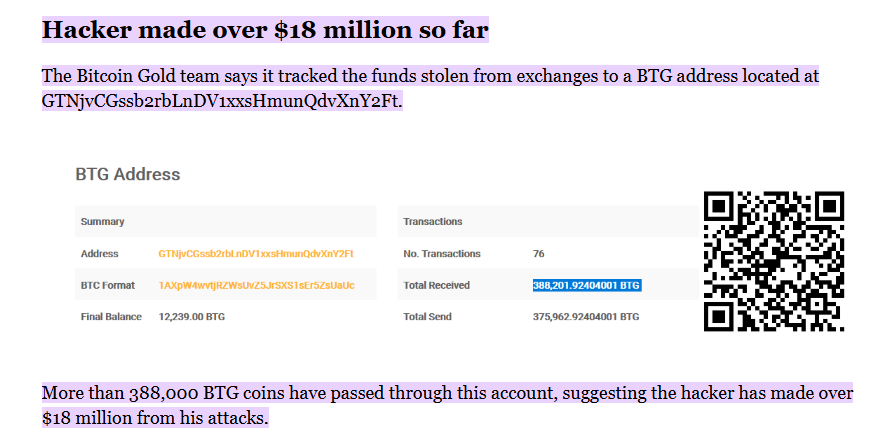

Another example is Bitcoin Gold (BTG). This project was created with the goal of “bringing Bitcoin back to GPU miners,” using the Equihash algorithm to avoid ASIC domination. However, because it can be mined with GPUs, hash rate for BTG is relatively easy to rent.

In 2018, a group of attackers controlled the majority of the hash rate and organized large scale double spending via exchanges, causing an estimated loss of around $18M. Notably, despite having already been attacked, BTG continued to face similar issues in 2020, leading many exchanges to lose interest in listing it.

This is a clear example of the lesson that if the cost of attacking is lower than the potential profit, attackers will be willing to return multiple times.

Litecoin Cash

In the segment of smaller forks, Litecoin Cash, Feathercoin, and several early altcoins are typical examples. These chains were forked from larger coins like Litecoin but did not build a strong miner community, leaving the total hash rate very low.

In such conditions, renting hash rate for a few hundred to a few thousand dollars per hour can be enough to gain majority control, build a private chain, and execute double spending. In some cases, the chain suffered repeated deep reorganizations, transactions were reversed, users lost money, token prices dropped sharply, and the projects were nearly “clinically dead.”

This group of cases shows that forking a new PoW chain is easy, but without building a security layer backed by sufficient hash rate, it will sooner or later become “prey” for 51% attacks.

When Bitcoin came close to 51% risk

Bitcoin has never officially suffered a 51% attack, but that does not mean it was always absolutely safe. In 2014, the mining pool GHash.io controlled nearly half of the total hash rate, at times reaching more than 40% and approaching 50%.

The community was alarmed because if this pool continued to grow or if a few large pools cooperated, Bitcoin could have entered a dangerous zone. Under public pressure, GHash.io had to voluntarily reduce its share of users and encourage miners to move to other pools.

Later, during the 2016 to 2017 period, mining pools based in China collectively controlled a large portion of the hash rate, prompting many people to ask whether Bitcoin could still be considered truly decentralized if these entities decided to act together. Although no attack occurred, these events reminded everyone that 51% attacks are not only a concern for small altcoins, but also an architectural risk inherent to every PoW blockchain.

Conclusion

Although the threat of a 51% attack still exists, and is theoretically possible even on large blockchains such as Bitcoin, the financial cost would be much higher than the potential benefit. Even if an attacker used all available resources to attack a blockchain, community detection and a rollback response would still be a possible way to mitigate the damage.

FAQs

Q1. Is a 51% attack the same as hacking a wallet?

No. A 51% attack does not steal private keys or break wallets. It abuses the consensus mechanism by controlling most of the hash rate to rewrite recent transaction history and perform double spending.

Q2. Why are smaller PoW networks more vulnerable to 51% attacks?

Smaller networks usually have lower total hash rate, so renting or concentrating enough mining power to reach 51% is cheaper and easier. That makes them more attractive targets for attackers looking to profit from double spending.

Q3. Can an attacker create unlimited new coins with a 51% attack?

No. Even with a majority hash rate, the attacker cannot change the hard coded supply rules or mint new coins arbitrarily. What they can do is reorganize blocks, reverse recent transactions, and monopolize mining rewards.

Q4. Has Bitcoin ever been successfully hit by a 51% attack?

Bitcoin has not suffered a confirmed 51% attack. However, there were periods when a single pool or a group of pools controlled a very large share of hash rate, which raised concerns about how close the network was to that risk.

Q5. What kind of damage can a 51% attack cause in practice?

The most serious impact is double spending through exchanges or large payments, which can lead to multi million dollar losses. It also damages confidence in the network, can trigger delistings, and in extreme cases can push weaker projects toward collapse.

Q6. Why is it so expensive to attack large PoW chains?

Large networks like Bitcoin have an enormous hash rate spread across many miners. Gaining and maintaining more than 50% of that power would require huge capital investment or coordination, often at a cost that exceeds any realistic financial gain.